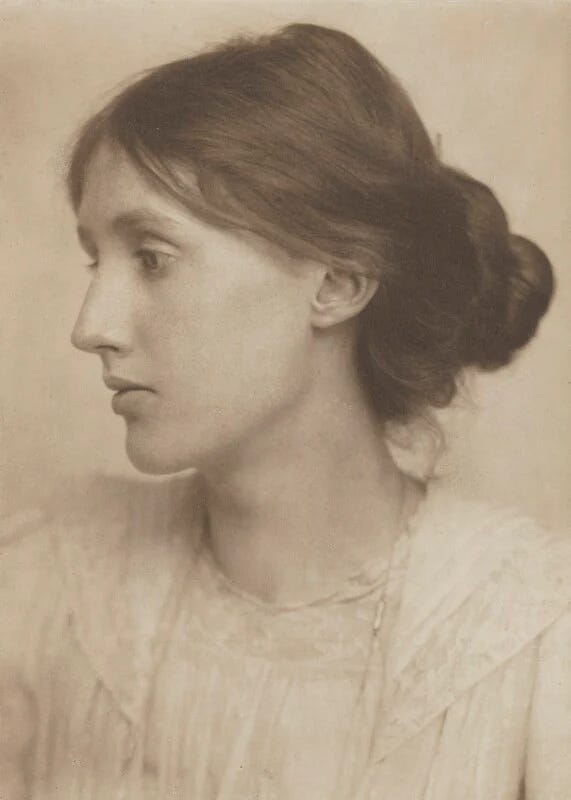

Whenever I go to the National Portrait Gallery I inevitably emerge clutching this portrait as a postcard. A photograph of a young Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford, taken in 1902, it is one of my favourite artworks. If I managed to keep hold of them, I’d probably be able to wallpaper the loo with all the copies of it I’ve owned. As it is, I mislay them, gift them and scatter them as I go about, a trail of calling cards for a life that isn’t my own, but which speaks so much to me of my own.

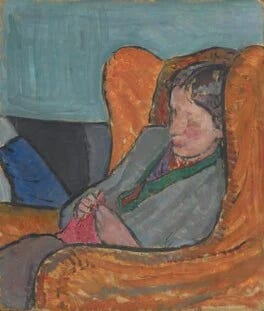

Here she is in 1912 in a portrait painted by her sister, Vanessa Bell. This is currently on display at the Gallery. I visit it a lot. I am obsessed with how in a few smudgy lines of paint you can clearly see who it is and how it relates to her earlier portrait. The tilt of the chin in the painting and the downward sweep of the eyes is the same. The painting radiates Virginia-ness. She exudes a kind of awkward knowingness, a bit like a badly furled umbrella. Practical but difficult to manage.

Here she is again in 1934, this time photographed by Man Ray (all these images are in the archives of the Portrait Gallery, who hold an extensive collection of pictures of Virginia). Her stalky angularity has sharpened over time, finessing the essence of who she is to a fierce collection of lines. Piercing is a word I think of when I look at her and certainly a word I think of when I read her. If she were an animal I think she’d be a hawk, sharp, knowing, highly strung, always hungry.

All of this brings me to Mrs. Dalloway, another entry in my sporadic attempts to write about my best books of all time (here’s the first). I’ve been thinking about it for a few weeks but couldn’t commit because I love so much of her writing. The London Scene, her collection of essays about London are an exquisite jewel box that I return to again and again. Even though they were written in the Thirties, enough of her London exists to make reading them and visiting the places she describes a small exercise in time travel. I went to Highgate Cemetery yesterday with a friend. As we walked through the memories of the dead, we were surrounded by the intense green of a thriving wood, birds calling between the rain showers and I though of Woolf: ‘ These garden graveyards are the most peaceful of our London sanctuaries and their dead the quietest.’

Then there’s Orlando, which is a truly astonishing novel. I am always surprised it doesn’t get as much recognition as I think it deserves. As a genre defying, time travelling, gender shifting love letter, it is surprisingly modern, way ahead of its time and an absolute icon of queer literature. It’s also funny and charming and enchantingly weird. To add to its delights, Tilda Swinton plays Orlando in the 1992 film and she is mighty.

And of course, To The Lighthouse, with its stunning juxtapositions, painterly images and its beautiful, burning anger.

She could have wept. It was bad. It was bad, it was infinitely bad! She could have done it differently of course; the colour could have been thinned and faded; the shapes etherealised; that was how Paunceforte would have seen it. But then she did not see it like that. She saw the colour burning on a framework of steel; the light of a butterfly’s wing lying on the arches of a cathedral. Of all that only a few random marks scrawled upon the canvas remained. And it would never be seen, never be hung even, and there was Mr. Tansley whispering in her ear, “Women can’t paint, women can’t write…”

But

, writing about Woolf yesterday gave me the nudge I needed to finally throw my hat in the ring for Mrs. Dalloway.In my final year at uni, I chose to study modernist literature for a term. It was one of those choices that wasn’t really a choice because everything else I had wanted to do in that time slot was already taken. Up to that point I hadn’t read much modern literature. It was an old fashioned university doing things the old fashioned way. We started with Plato, spent what seemed a lifetime looking at medieval literature, wasted at least ten lifetimes on Eighteenth century literature and finally eased into the Victorian triple decker novels with what was, for me, a sigh of relief. I knew exactly where I was with a Bronte sister. All my ‘modern’ reading was done for pleasure up to that point and I didn’t even know what constituted a modernist novel.

It turned out that a modern novel was surprisingly old. We started in about 1890 and cantered into the mid Thirties, where we came firmly to a stop, toes poking temptingly into a postmodern future we were encouraged to shun. We studied Joseph Conrad, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Franz Kafka, T.S. Eliot and of course, James Joyce. I enjoyed most things except Joyce, which I hated. I hated Joyce for lots of reasons. His bombast, his self-importance, his narcissism and his obsession with dirt. That man fucking loved dirt like a kink. Piss, shit, snot, grease, dust, muck, any kind of fluid a body emitted. He describes it all in forensic detail. I’m not disagreeing that he was a genius or that he could write. I’ve read everything he wrote with the exception of Finnegan’s Wake because life is too short, but dear God, he makes me sick to my stomach. If he were alive today, I have a sneaking suspicion he would be friends with Jordan Peterson.

We spent a lot of time focussing on Joyce and his use of stream of consciousness, a technique which some say he invented. It is the commingling of internal thoughts and feelings with external action and narrative, which means that you as the reader get to experience the inside and outside of what is happening simultaneously. I’m dubious as to whether Joyce invented it. I’d put my money on Laurence Stern’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman if I were a betting sort of woman. I’m fairly sure it gave Joyce a kick in the right direction in terms of Ulysses. (If you’re curious but can’t be bothered to dive into these two, mighty tomes, I recommend Michael Winterbottom’s film, A Cock And Bull Story for a flavour of what I’m talking about).

When we finally got round to the one woman on the course, Woolf, and her stream of consciousness classic Mrs Dalloway, I was expecting the worst. I braced for a torrent of narcissistic dirt birdisms and decided I would hate it. As soon as we started reading it I was like: ‘Oh! Now it all makes sense to me.’ I connected with it instantly. Where I actively backed away from peering into the minds that Joyce described, I stepped fully into Woolf, wandering about and marvelling at where she had put everything. I felt at home in her words.

Mrs Dalloway, like Ulysses, takes place over the space of a single day. Clarissa Dalloway is hosting a party. We follow her as she goes about her preparations, buying flowers, making her way through London, organising her staff, navigating social niceties and finally throwing her party. As she moves through her day we are privy to her thoughts and feelings, prompted by what she experiences in the now, but connecting and running away into her past and forwards into her possible future. These narrative tendrils ribbon out from Clarissa and touch the people she encounters, nudging their thoughts into play. Through that first connection we jump from mind to mind, from Pimlico housewives to shopkeepers, from aristocrats to newly arrived maids from the country. This kinetic way of narrating gives us a panoramic view of the London that all the characters move through. We see and more importantly experience their lives, their ways of being and seeing and what connects and divides us. Because we jump from character to character, all the while moving from inside to outside, past to present, present to future, we as the reader find ourselves inside the world of the novel far more readily than with a traditional first or third person narrative.

Woolf’s world is both painterly and cinematic. The smallest details are rendered vivid and meaningful. The tight, pale stretch of the sheets on Clarissa’s bed thrumming with her desire for a life of loving women, tamped down and suppressed in favour of the failure of living a fully realised marriage to her husband, Richard, nun like in its austerity. The constant references to doors and windows, railings and hinges, thresholds, things easy for some to pass through or turn to their advantage and for others an insurmountable block to progress. Glimpses of other lives run parallel to your own which you can only partially reach, things heard that snag on memories or the poignancy of opportunities lost. Some of those easy to live with, others unbearable.

Everything is saturated with meaning and connection. The flowers that litter the book from its opening passages filling the pages with their coded language, from the enthusiastic blooms of an early morning at the florist’s to Clarissa’s memories of the magical shock of meeting and falling for Sally Seton, who offers the promise of a different kind of life when she:

‘went out, picked hollyhocks, dahlias, all sorts of flowers that had never been seen together-cut their heads off, and made them swim on the top of water in bowls. The effect was extraordinary - coming in to dinner in the sunset. (Of course Aunt Helena thought it wicked to treat flowers like that.)’

Clarissa has been ill and the lives she could have lived but suppressed have begun to seep through as regrets and sadness, increasingly monopolising her thoughts. We can see the party as an attempt to celebrate and even force a return to health, or to inject the life she has ended up living with a joy belied by the narrow attic room and the increasing sense that not only had she picked the wrong life, but the life she has picked is moving rapidly towards being a kind of living death.

The other important character in this book is Septimus Smith. Septimus is a veteran of the First World War, a man suffering from shell shock and guilt at the intense feelings he has for his dead friend, the soldier Evans. Apart from his wife and an indifferent doctor Septimus is abandoned by a world who wants to get on and forget that the war had ever happened. The war has split him in two, just as Clarissa’s past has split her life. Clarissa and Septimus exist as the hinge to each other’s existence. They ripple back and forth as distorted reflections of each other. Clarissa teeters on the verge of madness but is able to use societal structures to haul herself back from the brink (for now). But from the first moment we meet Septimus, moving from mind to mind - from Clarissa in Bond Street across to Regent’s Park where the sound of a car backfiring is the starting pistol for the rapid disintegration of Septimus’ mind, Septimus is lost. The world that wants to hold Clarissa’s reality up has no interest in the raw intensity of the reality that Septimus represents.

Where Clarissa’s world is the language of flowers, cut and arranged inside the safety of houses, no matter how outrageously they may be represented, Septimus’ world is wild and dangerous, full of smoke and burning trees:

‘the excitement of the elm trees rising and falling, rising and falling with all their leaves alight and the colour thinning and thickening from blue to the green of a hollow wave…leaves were alive; trees were alive. And the leaves being connected by millions of fibres with his own body.’

Clarissa’s party is a success that allows her to right herself. But Septimus cannot live in a world that he feels so intensely and which is so painful. Unlike Clarissa, he has no facility left for dividing and locking down the parts of himself that make life so intolerable. The war never ended for Septimus, but everyone who could have helped him survive it is already dead. His suicide, throwing himself out of a window onto railings below is merely the physical manifestation of something he has done a thousand times before in his mind. The news of his death ripples through Clarissa’s party as their two worlds collide and then separate permanently. Clarissa comes to understand it as a sacrifice that allows her to keep living and it brings her a hard won, and to my mind, temporary peace.

In The Common Reader, Woolf says;

‘Life is not a series of gig lamps symmetrically arranged; life is a luminous halo, a semitransparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of consciousness to the end.’

Her writing explores the cast of that halo and the boundaries of that envelope, detailing the connections between mind and body, body and soul, art and life and from person to person. She has an unsurpassed ability to show how much we share as human beings but also the burden that opening ourselves to those shared emotions can be. She is acutely aware of the dangers of opening ourselves wide to the world if we cannot then find ways to retreat or create boundaries between ourselves and others. She shows how difficult it is for those of us who find the world overwhelming to carve out space for ourselves that isn’t punishing or isolating. Similarly she makes it clear how painful it is for those of us who love differently or want a different kind of life than society decrees to understand those differences but not be able to access the life we want rather than the life we have. It is a burden I think she felt herself and which ultimately broke her.

Thanks for this. I love Mrs Dalloway and you’ve reminded me why!

What a glorious exploration of VW and Mrs Dalloway. It’s so long since I read it and yet this brought it back so vividly. Makes me long for a re-read and to dive back into A Writer’s Diary. I may have to do that this weekend! Oh, and I have sneaking suspicion you’re absolutely right about Joyce.