As part of my ongoing obsession with lists, I occasionally attempt to make a definitive list of my favourite books. These lists are never finished because no sooner do I start thinking about a book than it opens the door for me to think about so many others, both read and unread. If I get further than the first five books, I then begin to think about how unwieldy the finished list would be, given how much I read, and how it would be better to categorise them by genre. That leads to a dilemma where I’m mentally holding a book in my mind, ready to shelve it here, or here and realise that it really needs to go in both places. It’s all too hard.

I decided instead to start an occasional series where I write about a book that definitely would be on one of my lists, if I was able to ever seriously get to grips with it.

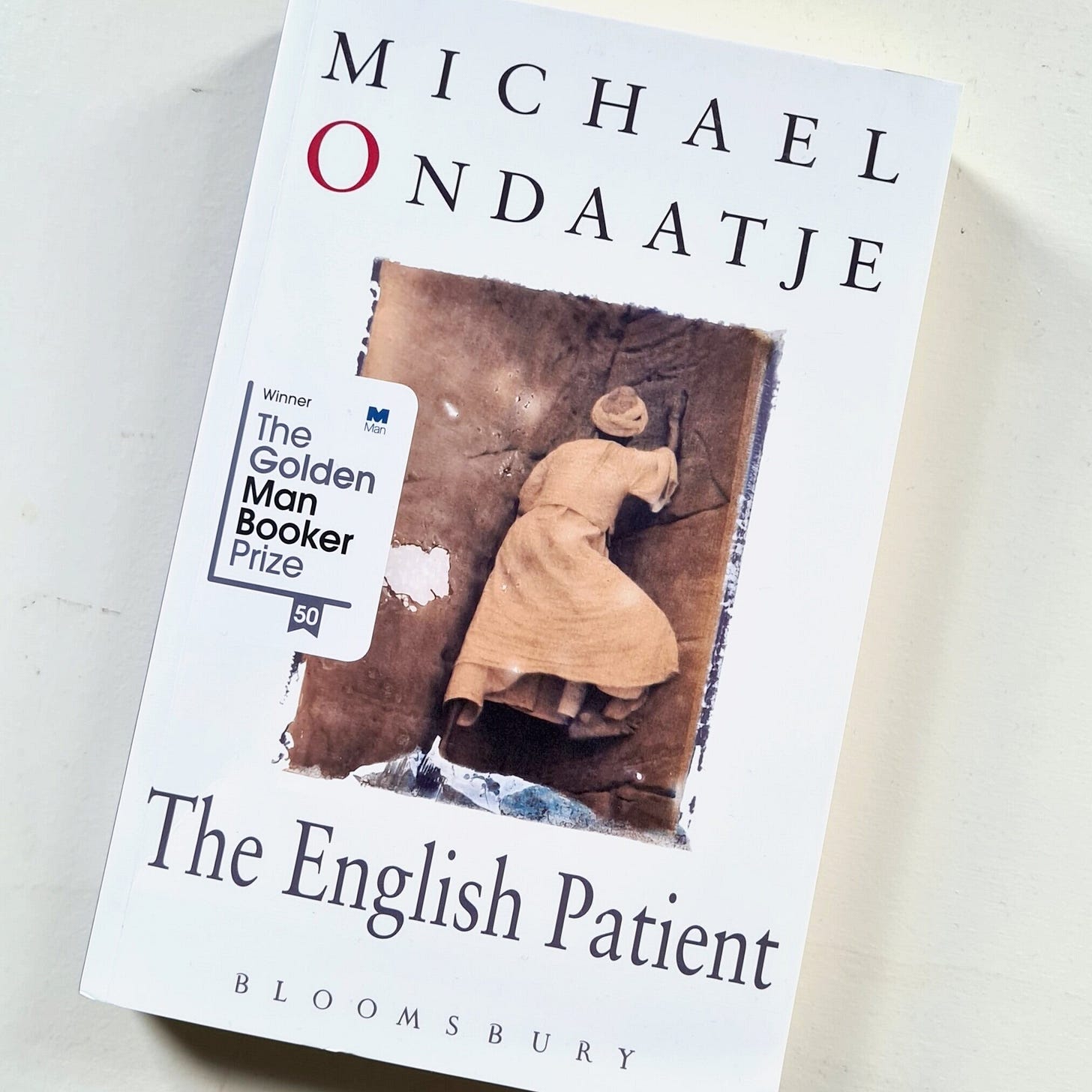

I’ve been thinking a lot about The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje recently. Written in 1992, it won the Booker Prize in the same year, and then the Golden Man Booker Prize in 2018. It is the sequel to his 1987 novel, In The Skin of A Lion, but you don’t have to have read either to make sense of the other. Ondaatje has a habit of populating his novels with recurring characters, which I rather love. It’s a bit like meeting old friends in unexpected places.

The titular English Patient is a severely burned man whose plane crashed in the desert towards the end of the Second World War. All he has on him is a copy of Herodotus’ The Histories. His identity is a mystery that his nurse, Hana is attempting to solve. The book opens with Hana and her patient left behind in an Italian monastery, while the allied troops are working their way onwards, liberating Italy. The patient is too sick to be moved and Hana volunteers to stay with him to the end. Discovering the patient’s identity and story is at the heart of the novel, but as the war rages outside and various outsiders arrive and depart, other stories become entwined with his, allowing Ondaatje to explore themes of belonging, identity, colonialism and connection amongst others.

The world of the novel is mutable. There are no clear boundaries. Hana nurses the patient in a room that was once painted to resemble a garden. The monastery is crumbling, insides becoming outsides and outsides reaching in. Kip, the Sikh sapper, dislocated from his own country, works to stabilise the uncertainty of the bomb mined country around him. The ground here cannot be trusted. The patient is burned so badly that bone is visible. His insides become outsides too and his outside is unrecognisable. In patching together his memories he tells Hana:

‘I fell burning into the desert.

They found my body and made me a boat of sticks and dragged me across the desert. We were in the Sand Sea, now and then crossing dry riverbeds. Nomads, you see. Bedouin. I flew down and the sand itself caught fire.’

Throughout the book, one thing turns into another. A spy is a thief, an addict becomes a saviour, an outsider steps inside. The desert, which was once a sea becomes a different kind of sea. Boundaries constantly shift and change. Throughout the book the question of identity is a constant refrain, but how can you say who you are and where you’re from when the war has turned the whole world into an uncertain desert that could burst into flames at any moment? The boundaries which held you steady, have burned away and now you are loose in a world where anything might happen and you might become anybody.

In a book which is set largely in the desert, water is everywhere. A ‘waver’ of light, the smell of liquid in the air at an oasis, a wave of glass, the rain falling into a bombed out library, the ‘swimming’ motes of dust in the air. This tug of memory and the notion of liquidity, telling us that the land we have taken for granted for so long can transform, has transformed and will do so again and again. The stories of Herodotus and the stories of the war are equally mythic and viable here. Past and present blur and the wide arc of history concertinas into something tangible and precious. The land soaks it all up, enduring where we fail, changing and yet somehow, inevitably, remaining the same. This is the spell of this book.

As the narration moves forwards and backwards in time, we are caught in intimate moments that nestle up against vast, sweeping events. The discovery of the patient’s doomed love affair plays out against the backdrop of the war. Hana’s budding relationship with Kip echoes it, like an elegiac refrain. We know that without the war, neither of these relationships would have started but what can survive against this onslaught of violence and fire? The haunting beauty of both relationships has loss at their heart. The end is built into the beginning. The physicality of their connection comes apart against the brutal violence of the landscape against which it is played out. The bodies fade and then what is left?

Whatever does survive is changed in ways that are unrecognisable and strange. The sea becomes a desert over and over again. The world is always on fire, but there is hope. There is hope in the pages of Herodotus. There is hope in the ways of the Bedouin tribes that have learned to survive in a waterless land where fire rains down from the sky. There is hope in the human connections that change us even though we cannot always survive them in the form we know now.

My favourite passage is one that sums up the point of the book in a few, exquisitely rendered paragraphs. The patient recalls, in the language of a miracle, salvation visiting him in the desert.

‘One night he heard what seemed to be wind chimes high in the air, and after a while it stopped and he fell asleep with a hunger for it, that noise like the slowed-down sound from the throat of a bird…

The next day he heard snatches of the glassy sound as he lay once more covered in cloth. A noise out of the darkness. At twilight the felt was unwrapped and he saw a man’s head on a table moving towards him, then realised the man wore a giant yoke from which hung hundreds of small bottles on different lengths of string and wire. Moving as if part of a glass curtain, his body enveloped within that sphere.

The figure resembled most of all those drawings of archangels he had tried to copy as a schoolboy, never solving how one body could have space for the muscles of such wings.’

I went to see the film when it came out, worried that it wouldn’t be as good as the book, but it is one of those rare occasions where I feel that it was perfectly done. The image at the top of the post is a still from the film, depicting cave paintings of swimmers in the desert that was once a sea. It, like the book reminds us that anything is possible and everything will change.

I cannot tell you how much I love this book - so much so that I can’t bear to read it again.

I watched the film again a couple of weeks ago for only the sevobd time. I first watched it in the cinema when it was released, and then read the book, which is all a very long time ago. Both the book and the film are exquisite and your review is a wonderful tribute.