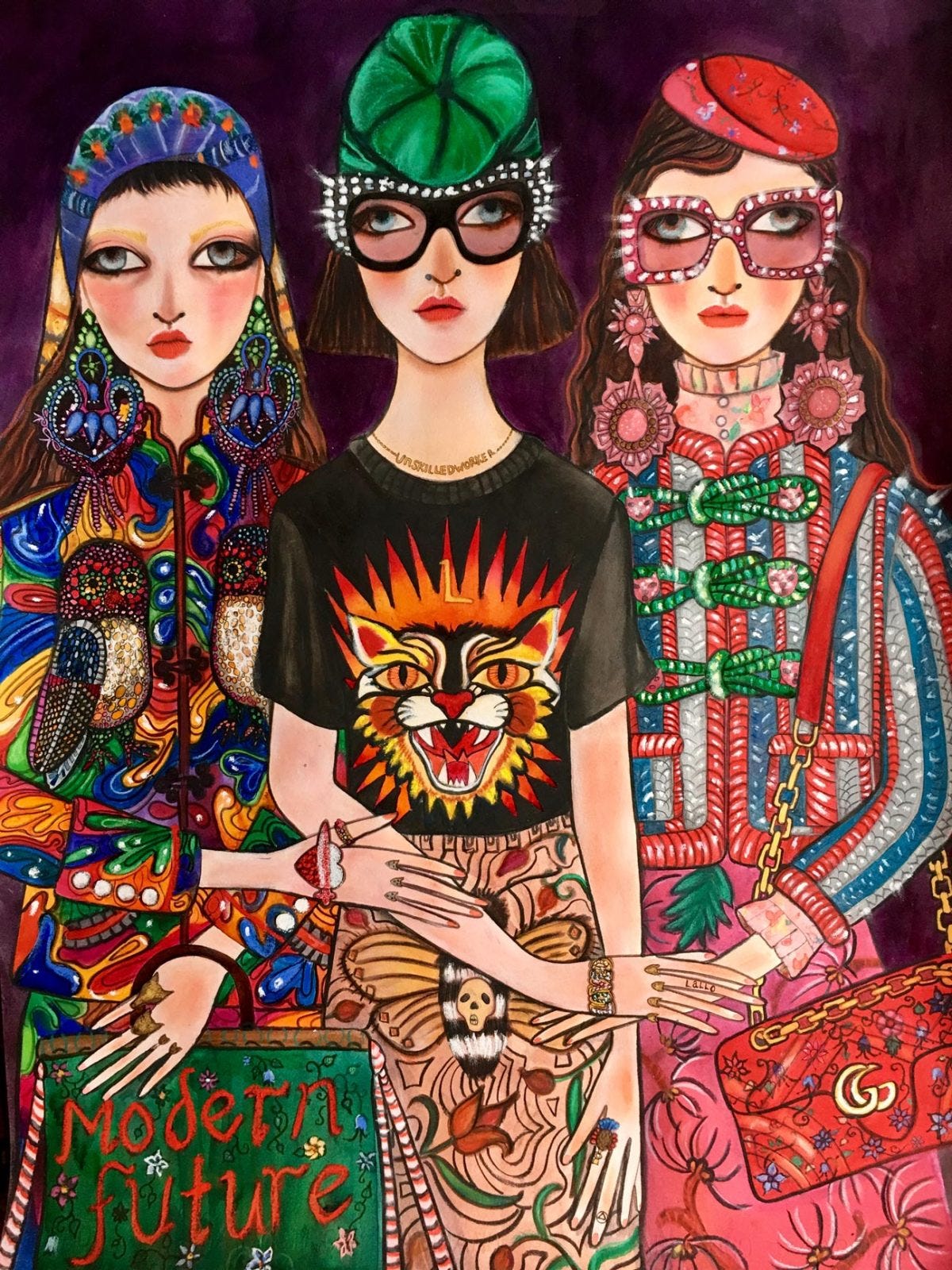

Recently I’ve been excited about an artist called Unskilled Worker (Helen Downie). I discovered her through listening to Katy Hessel’s Great Women Artists podcast and have been thinking about her ever since.

She didn’t start to paint until she was 48 (in 2013) and has painted obsessively ever since. She started painting faces, taking inspiration from the fashion industry which bore fruit when her Instagram account was discovered by photographer Nick Knight. She went on to collaborate with Gucci and her career has flourished across fashion and art ever since.

I am fascinated by her late start. I’m always interested in people who come to their passion later in life. The older I get, the more inspired I am by people who pick up new skills with age. It gives me hope that I still might find my passion in the years to come.

What Downie said in the podcast was that she felt that it was only in later life that she had the space in her head that allowed for the painting to happen. I have certainly felt with every year that has passed since my hysterectomy, that there is more room inside me for me. I once read a book about menopause, where the author said that after menopause our bodies reset hormonally to where we were before we puberty conspired to drive us mental. Only, unlike when we were children, we have agency and the means to make the most of it. That’s what these paintings seem like to me, both the act of making them and the paintings themselves.

Downie talks about painting for her seven year old self and using her art to explain to that child where life had taken her and how to make sense of it. I love that. I love that her paintings are clearly so fulfilling and so personal to her. They show, she says, a world that might exist. I think it does exist. I think her paintings show life on the inside and the outside simultaneously. They translate thought and feeling into colour and shape, real things against maybe things and want to be things, what is happening now, shaped by what happened then. They are exuberant and colour filled, bursting with the need to express what has been inside for so long. They feel like a way of marking a life well lived, for better or worse.

I keep wanting to use the word naive in relation to the style of the paintings, but I hate the way the word often gets used to express a kind of patronising amazement that someone untrained can hold a brush, and that’s not what I mean at all. Maybe it’s that they exude a sense of wonder, like when a child discovers something they find brilliant. When I look at the paintings they remind me of Sylvia Plath’s poem, Child:

Your clear eye is the one absolutely beautiful thing.

I want to fill it with color and ducks,

The zoo of the new

Whose name you meditate —

April snowdrop, Indian pipe,

Little

Stalk without wrinkle,

Pool in which images

Should be grand and classical

Not this troublous

Wringing of hands, this dark

Ceiling without a star.

As with the poem, in amongst the wonder of the art there is a darkness lurking in these paintings. Sometimes in the eyes of the subject you detect an old kind of sad knowingness in this joy. It feels hard won and tinged with melancholy. Later in the podcast, Downie talks about painting friends and loved ones who have disappeared from her life for various reasons as a way to reconnect and find them again. They are a spell, a painterly conjuring with a true sense of magic them.

For me, the paintings and their purpose feel folkloric. Folklore has always been a way of attempting to explain the unexplainable. I think that it has a more female energy than myth. It wrestles with our deep seated need to understand the primal forces that animate human beings and what binds them to the to the land and life that shapes them. It talks about life and death and all the strange paths that connect the two. In the world of folklore you can mix magic porridge pots with wolves that want to eat you for not being a good girl. Green men get their heads chopped off and are reborn, the goose girl is really a queen. The every day sits with the uncanny, sometimes side by side, sometimes overlapping. I see this world in these paintings, just made new for the modern world.

Towards the end of the podcast, Downie talks about the mystical side to painting and her belief that there is a transference of energy that takes place when someone stands in front of a painting that moves them in some way. In the seeing there is a knowing that creates a bridge between the artist and the viewer and allows us to experience the work in a deeper, more meaningful way. She also talks about love, about throwing a whole heap of love at the paintings as she makes them - and that’s certainly a big part of what I feel when I look at them. They’re magic.