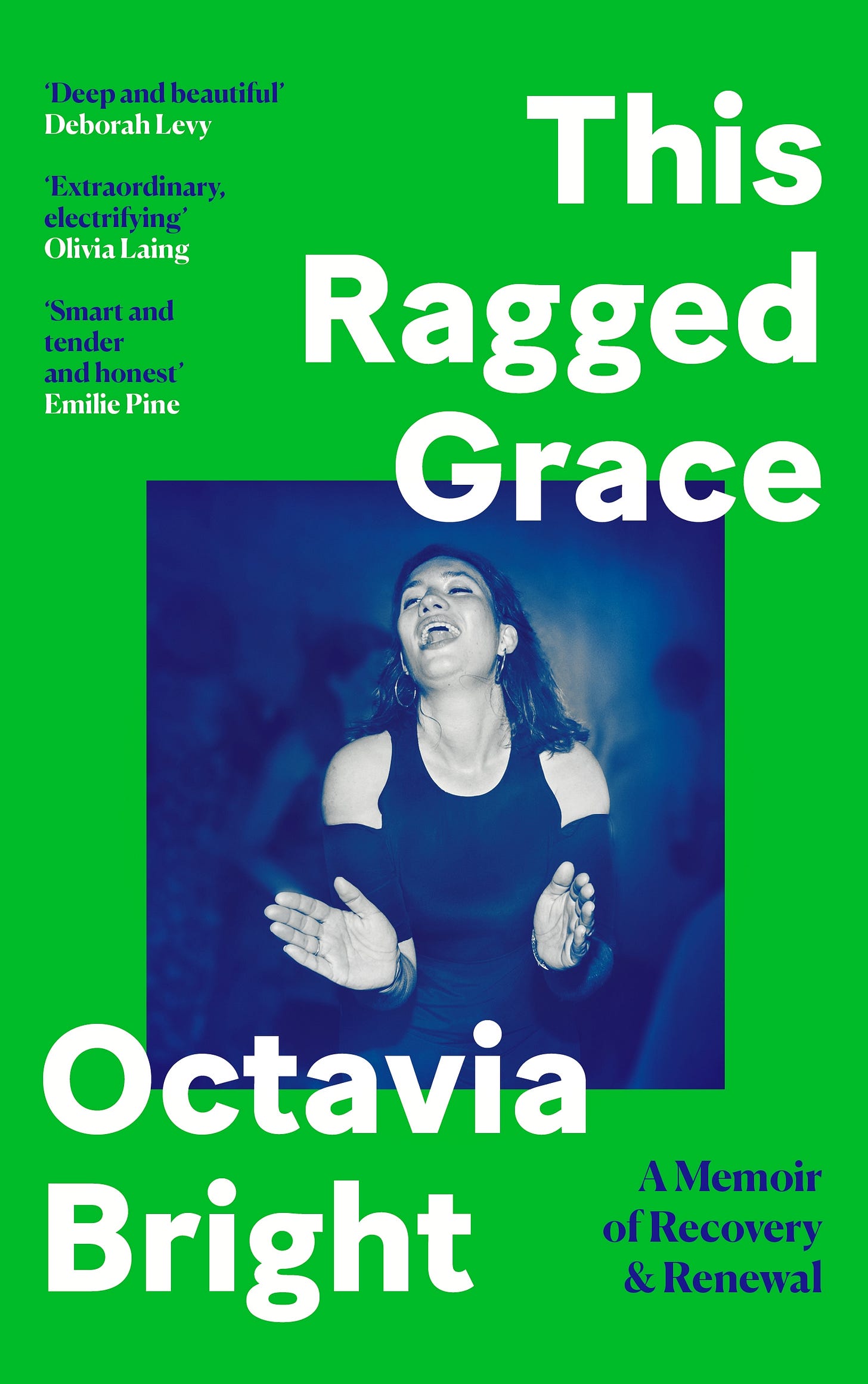

In This Ragged Grace, Octavia Bright’s superb memoir of addiction and recovery, she says:

‘There’s a startling power in recognising your own internal life in someone else’s words or images.’

It summarises my reaction to this book better than all the words I’m about to write.

I’ve talked about the power of seeing myself in the writing of Sylvia Plath as a mad teenager and in middle age, finding myself in the words of Thom Gunn. Bright is a welcome addition to the writers, artists and makers who shore me up against my ruins. She says:

‘Every story you tell yourself is an attempt to organise the messy experience of living.’

Which is exactly what I am attempting. The lifeline that is other artists and writers who touch the tender parts of your soul, like Bright, is that they offer you a springboard from which to dive deeper into your own experience. They also remind you that there are people waiting for you when you come back, even if only in the pages of a book.

Life is a lonely business if you’re not blinkered into the norm. As E. M. Forster so beautifully put it, life becomes tolerable if we ‘only connect’. That can be hard if everything in you tells you that you are damaged, dangerous and alone. That ‘you’ is hard to accept and even harder to thrust upon other people. The fear of rejection is a powerful curb to honesty and vulnerability. There is a reason punishment thrives in solitary.

The irony is that the more we hide this untenable part of ourselves, the more isolated we become regardless. We become the prison guard and the prisoner. Recovery is a slow, repetitive process of unlocking whichever cage we happen to find ourselves in and walking out, one step at a time, into vulnerability, truth and connection. It’s fucking terrifying. It’s like being the naked Emperor on walkabout but with the full knowledge that your suit is a fiction.

Bright’s drug of choice is alcohol, mine are co-dependency and spending. She is excellent on the sweet, sweet rush of addictive behaviours. The relief at scratching an itch that becomes so intolerable you can think of nothing else. The unsurpassable high that starts so gleefully. With luck there’s an ensuing baffle between you and reality that comes with indulging your need, and it is a need. It might feel like a desire, but it’s an illusion. A dangerous one at that. We succumb to desire. We are in thrall to need.

That’s when we get to the horror of diminishing returns. The spiral of shame that shunts the behaviours into a tighter and tighter coil that snares you as it relieves you. The grimy squalor of your thoughts. For a while, from the outside you appear to soar and shine. On the inside you can always feel the tilt and plummet. Bright describes it as an ouroboros, the symbol of the snake that eats its own tail, forever.

A few years ago, my daughter was being treated for an eating disorder. Initially we had a session of family therapy to discuss the impact of her condition on us. We were each given a sheet of paper with the outline of a body on it. We were asked to imagine it was her and fill in how much we felt of her was herself and how much was her addiction. It was frightening to see how much we each felt we had lost of her. Addiction, whether it be through what we allow or deny ourselves, if left unchecked, begins to erode who we are. We start to become what we do to ourselves.

This makes it very hard to recover. Bright quotes Graham Greene in The End of The Affair.

‘What happens if you drop all the things that make you I?’

I know this fear so well, I can taste it.

One of the biggest traps of addiction is the confusion of doing with being. Doing is often the very thing that stops us from being. In a world that increasingly demands more and more of us and wants tangible, measurable results of some kind of success, just existing becomes harder and harder. The society we find ourselves in is fertile ground for addiction to flourish. Everything is loud, everything is bright, everything is now and now and now. If you’re trying to find some kind of authenticity of self in all the din it can be extremely daunting.

Bright’s memoir is so brilliant because it is this work towards authenticity that takes up most of the book. Recovery for her, for most of us, definitely for me, is not a nice, linear graph with a steep, upward trajectory. It’s more like the way a raindrop courses down a windowpane. It meanders and splits, it trickles and stops, it dribbles and shunts its way into other streams. Recovery is organic and ongoing. It’s a daily practice in every sense of the word, because it is far from perfect.

The pathos of Bright’s recovery is that it sits alongside her father’s plunge into dementia. She uses the language of addiction to describe what dementia takes from a person and their loved ones and it felt so apposite. Addiction both gives and takes. To begin with you gain more than you lose, but the odds are never in your favour. Bright describes the dementia taking away the man she knew as her father, but recovery empowering a new and ever changing relationship with the father he is becoming.

People often make the mistake of thinking that being is easy. That’s because most people don’t spend a lot of time being. Being present in the life you have rather than the life you want or the past you lived through is extraordinarily difficult. Recovery gives you the tools to manage it. Being is not passive in any way. Sitting in the present moment with someone exactly as they are and yourself exactly as you are can be excruciating. Accepting yourself with all your flaws whilst not putting up with any of your shenanigans and doing the same for others, is painfully hard. If you’re like me, you do it over and over and over again and still you fuck it up and have to start again. I spend much of my life feeling like a Doolittle Pushmi-Pullyu. About twice a year I feel fully centred. Then I wobble off into the next challenge.

What makes it so difficult to recover is that all these internal negotiations sit alongside whatever is going on externally. In Bright’s case, her nascent career, her love life and more than anything, her relationship with her father. You don’t get time off to figure out how to be yourself.

For me, I’ve negotiated madness, five miscarriages and an ectopic pregnancy, three births, marriage and divorce to an alcoholic (now sober), remarriage, my daughter’s eating disorder, my father’s stroke, my son’s best friends’s suicide and countless other events, large and small that have all challenged my ability to stay sober in my own way. I have absolutely failed on more occasions than I care to count. Co-dependency is a particularly tricky addiction to manage when you have children who you have to care for, but also have to stop caring for, but only some of the time.

The joy and pain of active recovery is in the connection. Addiction severs us from life, but it also simplifies it because at the end there is only ever the addiction and feeding it. Recovery reintroduces life and takes away that beautifully numbing cushion between us and the world, but it also give us back the world to make anew.

A lot of recovery feels like barking your shin repeatedly against the same table. Your skin is thin. You feel everything, all the time. It is big and unwieldy and you feel small and puny. What can you do?

For me, recovery is a lot like a clumsy dance. I pick up. I put down. I accept. I push back. I allow. I create boundaries. I control myself. I relinquish control over others. I feel, but I don’t always act on those feelings. I accept that I don’t have any control over what I feel but that I do have control over what, if anything I do about it. I sit with what makes me uncomfortable. I move forwards. I try to put the past where it belongs. I fall down. I get up, over and over again. I own my stuff. I make amends. I give back what doesn’t belong to me. I try to do better. I look at what makes me want to pick up my addiction and attempt to heal myself without using.

I get it wrong all the time. I acknowledge my fuck ups. I forgive myself.

I write to hold myself accountable. I read to remind myself I am not alone. I try to tread the line between sharing everything and hiding everything. I think about Bright’s quotation by Marlene Dumas.

‘At the moment my art is situated between the pornographic tendency to reveal everything and the erotic inclination to hide what it’s all about.’

I give thanks for people like Bright and Dumas and Greene. They are not me and I am not them, but their words help me to be more me. Sometimes they just help me to be.

This is really beautiful writing, Katy. Also the co-dependency in relation to children is something I think about a lot and I don’t think people talk about enough. It’s so hard.