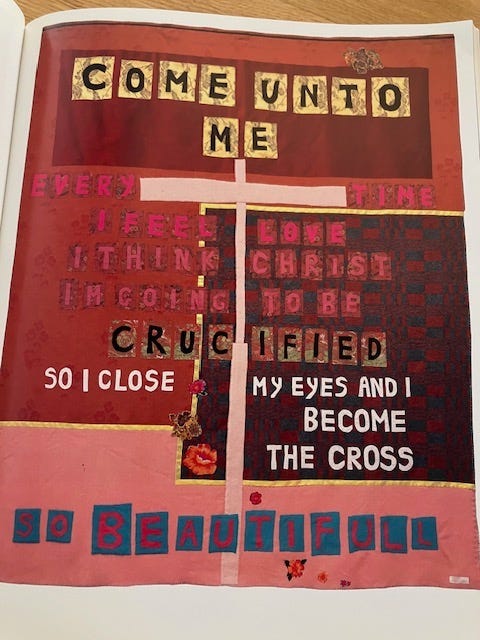

I was reading Tracey Emin by Neal Brown when I came across the image of this quilt. It’s called Automatic Orgasm from 2001.

Quilts is where I started to fall in love with Tracey. I have been into quilts for a long, long time and when I first saw hers in an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, I went from mild interest to I love her and want to climb inside her brain in about ten seconds flat. I love everything she makes, but I have a particular fondness for these, early works.

One of the things we learned during my Art of Looking Course was to think about an artist in relation to their whole body of work. So many of us look at one or two pictures by an artist and make the assumption that we know them. Then we make a decision about whether we like or dislike them based on that. Sometimes we never revisit their work, because our decision is made. That now seems criminally shortsighted.

I’ve been guilty of it. I still am. Although, thanks to the course I am creeping up slowly on being less judgmental. That’s only in relation to artworks, mind you. Painted people are easy to reassess, my relationships with real life people is much more adamant. I’m not declaring my sainthood just yet. Although the reliquary business is very alluring. Who wouldn’t want a saint’s finger on a gilded stick?

Often, if an artist is lucky enough to have a long career, they will produce vastly differing work depending on where they are in their life and what they want to say. Using the example of Philip Guston, our teacher, Rose, took us from his first paintings, which he produced at a sickeningly precocious fifteen, through his entire creative life. It was interesting to see that even though his style evolved dramatically, the things he thought were important remained. The changes in the way he depicted his subject were actually a distillation of his thought processes. His work seems on the surface to become simpler, but actually, it is that he found the visual language to make his thoughts and feelings more sharply concrete with greater economy. His early work is gravy. His later work is a stock cube, as it were.

With this in mind, I think it is possible to see in Emin’s work an evolution of style that moves from the explicitly graphic world of the quilts and films to the paintings and sculptures she makes today. I have written about her paintings before, and see that I had begun to explore that evolution already. The means of making are different, but the themes and ideas have become so embedded they can now be explored and explained in a sweep of paint. It feels like the work and the language of the work have become the same thing. I find that a pretty beautiful idea.

One of the wonderful things about having access to artworks is the ability to revisit them. Siri Hustvedt talks about this in her interview with

on The Great Women Artists podcast. Even though an artwork may be a static thing, we as the viewer of it, are not. As we grow and change, works which didn’t speak to us when we were twenty, may connect with us when we are thirty or forty, and hit in a different way in old age. Every time we see a work, we bring all that we are in that moment to it, which is why art can endure where other things fade. We read what we need, we see things in different ways depending on the who we are when we rock up in front of an artwork. Art appreciation is something I think of as an ongoing conversation rather than a tick box exercise.That’s where I come back to the Automatic Orgasm quilt. For Emin, it is an exploration of the idea of her sexuality and relationships in the language of religious rite and sacrifice. The language of transcendence and the sublime is a religious idea that maps precisely against the language of the body and the otherworldly, weirdly out of body feeling that an orgasm gives you. The act of giving yourself to someone else, of surrendering the body and releasing something that is bigger than the physical does correlate to religious ideals. The sacred and the profane are one and the same. One of the things I love best about Emin is her ability to toggle between art and life, the physical world around her and the world of emotion and spirit and the co-opting of concrete materials to express the inexpressible. These are themes she is still exploring today.

With the quilts there is a matter of fact quality that you can’t really argue with. There’s no ambiguity here. You are confronted with a double bed sized quilt covered in exactly what she wants to say. But that doesn’t mean that it’s all there is to it. If it’s all there was, the art wouldn’t have the power of endurance that it does. It would be no more or less than a graphic t-shirt or a stick of rock with ‘A present from Margate’ running through it.

For me, looking at this work recently, I thought about the wider idea of sacrifice. I thought about the fact that women, in particular, are taught that their role is one of giving until it hurts, not just in terms of their sexuality, but in every aspect of life. I thought about the mother of a boyfriend I had in my twenties, who would cook delicious meals for her family, but would only eat the leftovers from the day before herself, so that it didn’t go to waste. I thought about all the times the school had rung me when a parent was needed, even though my husband’s phone number was on the emergency contact sheet, and how I dropped everything and went to the rescue, every time. I thought about my dad’s stay in hospital over the last few days and how hard it was for me to step away from being on the front line, even though other people were around and willing to help.

Tracey stitches: ‘Every time I feel love I think Christ I’m going to be crucified, so I close my eyes and become the cross.’ It’s ‘so beautiful’ she concludes. I wonder if it really is? Or is that the best we can do with the suffering and pain we take on?

Previously, I found this message quite comforting. There’s been a lot of suffering in my life that I’ve been unable to avoid, or incapable of dodging with the tools I had at the time. I totally get why there is such allure to finding it beautiful. There has to be ways to tolerate what seems otherwise intolerable. I think about the photograph of Robert Mapplethorpe which I briefly wrote about here, and which I explored more deeply on my art course with Rose. I find the photograph attractive at a visceral level. It makes death seem inviting and somehow controllable. Of course, this is useful when you are, or in this case, Mapplethorpe himself, is suffering and facing the death sentence of AIDS. There has to be some beauty in the pain, otherwise the pain becomes intolerable but it still has to be endured. This is where the art comes in. It allows the artist to take the pain and transmute it, even if it is an illusion, it is sometimes a helpful one.

The Mapplethorpe photograph, and to an extent, the Emin quilt, make me think of the poet, Thom Gunn’s work, The Reassurance, from his book The Man With Night Sweats, which deals with the impact of the AIDS crisis.

About ten days or so

After we saw you dead

You came back in a dream.

I’m alright now you said.

And it was you, although

You were fleshed out again:

You hugged us all round then,

And gave your welcoming beam.

How like you to be so kind,

Seeking to reassure.

And yes, how like my mind

To make itself secure.

For me, right now, all these works provoke me to think about the nature of sacrifice and its role in my life. I think of all the times I have justified it, to ease my pain. I think about all the times I have demanded it of others. I think about the wider, social conditioning that so often makes this a peculiarly female arena. I think about all the things I have learned and, until therapy and looking at art, have shoved down into my subconscious mind, where those things have often steered me into situations I could otherwise have avoided. Now though, I am looking at things in a different way and bringing ideas to the surface, where I can decide what I want to do about them instead of allowing them to decide for me.

In the hurly burly of hormones, child rearing and other external pressures, there didn’t seem to be any time to think, but now, things are different. I am post menopause, my hormones have left the building. The great, jarring pull of sex is not a thing anymore. The lure of my bed as a place to sleep is much stronger. My kids are grown and my family need me in different ways which give me time to think and time to start a different conversation with myself and others. Just as Emin co-opts the language of religion to explore her sexuality, I am co-opting the language of art to explore the notions of sacrifice and other drivers that have shaped my life and think about what I might want to do differently in future.